NORTH STARS:

Waste Management

Carbon Footprint

Water Management

“For millennia, people all over the world made wine using whatever wild strains happened to be clinging to the grapes before they hit the fermentation tank.“

As a long-time observer of the wine industry, I can say only a few things with absolute certainty: outsiders love to romanticize the art of making wine, insiders love to perfect the science of making wine, and wine itself—and the people who make it—will never stop surprising me.

OK, there’s one additional bulletproof observation to share: vinters have an unparalleled talent for making winemaking science feel artful.

Take yeast: dried, commercial yeasts were developed in the 1950s by labs in Canada and the U.S., and since then, more than 100 strains have been made widely available to wine producers around the world. Winemakers typically use commercial yeast during the fermentation process.

While commercial yeasts are preferred by many for their uniform, predictable results, others spurn them for the exact same reason. For millennia, people all over the world made wine using whatever wild strains happened to be clinging to the grapes before they hit the fermentation tank.

And yet wild or indigenous yeasts aren’t always exactly what a vintner wants either, because the results can be unpredictable. Sometimes fermentations with wild yeast are painfully slow, creating opportunities for bacteria to come in, join the party and bring an often unwanted panoply of funky aromas and off-flavors.

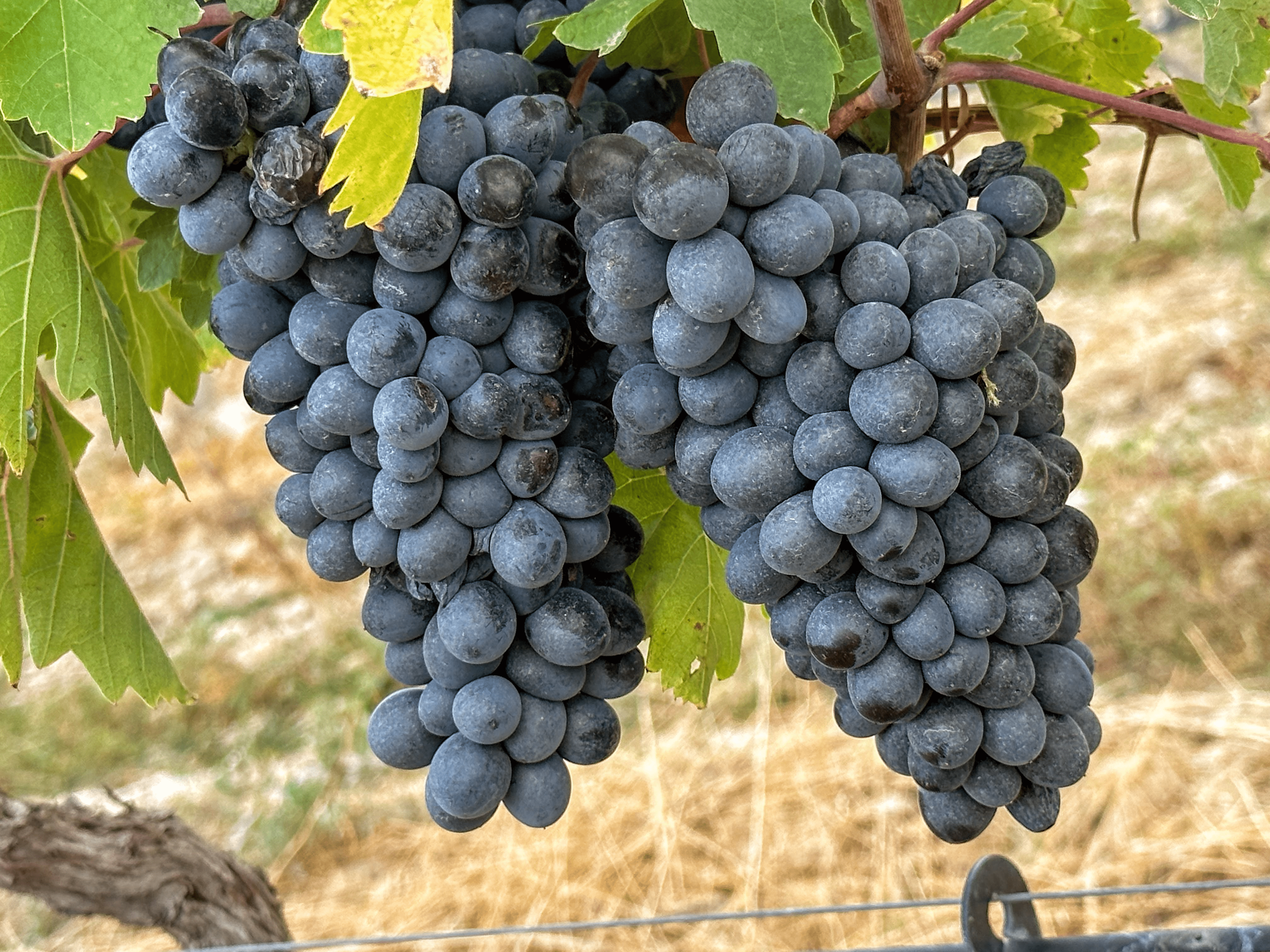

Ripe grapes on the vine have local yeast on the skins. Image by Lauren Mowery.

Going Wild, Predictably

A growing body of winemakers have found ways to get wild, without going feral. Wes Andrew, winemaker at Atwater Vineyards explains. Atwater is located in Burdett, NY, and has 40 acres of grapevines, with a handful of long-term contracts with growers in the surrounding Finger Lakes vineyards.

“Around 2015, we started tinkering with the idea of a Pied de Cuve, mostly for smaller batch projects at the time,” he says. “It wasn’t until 2021 that I had the opportunity and freedom to build a much larger Pied de Cuve program and use it on larger lots of wine,”says Andrew.

A Pied de Cuve, for the uninitiated, translates literally as a foot to the tank. Comparing it to a sourdough starter in bread baking, Pied de Cuve provides the ‘kick’ that grape must (freshly crushed grape juice) needs to start fermenting.

“The point is to capture wild yeast that is in the vineyard and on the grapes so we can create a culture to kickstart our fermentations, instead of using cultivated yeast,” he explains. Essentially, this method is used by winemakers who want to use wild but predictable yeast.

Andrew and his team create batches of Pied de Cuve in the first week of September. The team typically picks a small amount of grapes, crushes them, allows them to ferment and then creates a “starter culture” of native yeasts. Small portions of the Pied de Cuve can then be added to grapes post-harvest to kick off fermentation.

Since 2015, Andrew says he has ramped up his use of Pied de Cuve, and now uses it for almost all of their wines including whites and rosés.

“Most of the fermentations are slower,” Andrew observes. “It allows us to capture wild yeast while still allowing for a clean start to a fermentation, similar to a commercial yeast. For me, using Pied de Cuve has become a ritual and a mantra. It’s about using what you’re given and making the best out of it.”

Harvested grapes in a bin. Image by Lauren Mowery.

A Pied de Cuve does more than just kick up fermentation. It also underlines and accentuates the sense of place, or terroir, of a vineyard and winery.

“In most cases, the yeast in a Pied de Cuve is unique to that specific vineyard and arguably that particular vintage,” says Andrew. “If that’s not a reflection of terroir, then I don’t know what is. I try to make wines that are as reflective of their place as I possibly can, but also to make a good, clean and acceptable wine in the process, and utilizing a Pied de Cuve does both.”

A wine that reflects both the time and place in which it comes from does look, feel, and taste like an art. Using a pinch of science to get it done with consistency and efficiency—but not too much?

That’s a real kick to the tank.

Kathleen Willlcox writes about drinks, travel and culture from her home in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and from the road, while exploring. She is keenly interested in sustainability issues, and the business of making ethical drinks and food. Her work appears regularly in Wine Searcher, Wine Enthusiast, Modern Farmer, The Drinks Business, Wine Industry Advisor and many other publications. Follow Kathleen on IG @kathleenwillcox.