NORTH STARS:

Gender Equality

Community Support

Heritage Value

“The unfamiliar words that he chants in the Naso language swirl around my head like the smoke he uses to bless me. I inhale the thick, acrid fumes and exhale anxiety, fear and doubt.”

A spray of muddy water hits my face as the cayuco navigates a challenging stretch of the roiling Tjerdi River. Bloated from recent heavy rain, the river pushes its way through the thick jungle that is the ancestral land of the Naso, the last Indigenous traditional monarchy in Latin America.

The cayuco, or small canoe, in which I’m seated is ferrying me downriver, back to the remote community of Bonyic where I’m spending time with the Indigenous Naso tribe, one of seven semi-autonomous tribes in Panama, and one that’s welcomed visitors since 2012. There are sixteen Naso communities here — in this small slice of Bocas province — tucked far into the jungle. Despite their ancestral roots running deep, they weren’t granted communal ownership of their tribal lands by the Panamanian government until four years ago.

To get there, a group of international travelers and I joined Eco Circuitos, a Panamanian company that organized the journey and logistics. We flew from Panama City to the island of Bocas del Toro and caught a 30-minute boat ride before a further 60-minutes of driving took us to this off-grid community.

Panama Jungle Trails. Courtesy of Pexels

A New Way to See Panama

The most common way to travel between the communities is by boat, with traditional, hand-carved cayucos now outfitted with outboard motors to navigate the river’s Class II rapids. However, a new project is underway to change how locals and tourists move through and connect with the land by revitalizing ancestral trails.

Started in 2022, the 1,000 Kilometers of Trails project aims to develop over 560 miles (900 kilometers) of trails around Panama over the next five years. Spanning both land and sea routes, the project aims to promote outdoor recreation, boost local tourism, and safeguard cultural heritage. Along with developing new paths, the network will also incorporate and connect historic trade trails once used to transport gold and other goods during Spanish rule.

Connecting Travelers and Communities

“Outdoor recreation [in Panama] isn’t quite as popular as it is in the States and Canada,” says Adrian Benedetti, director at the Asociación Naciónal para Conservación de la Naturaleza (ANCON), and the driving force behind the project. “It’s not really part of the culture.”

Along with hoping that hiking and outdoor recreation become more entrenched in local tourism, he also hopes that communities along the trails become invested in the project’s long-term success and its potential to support and sustain traditional culture in remote areas.

“The easy part is the building,” says Benedetti. “The challenge now is how are these trails going to be managed moving forward?”

To do this, Benedetti ensures that local communities are fully involved in the trail-building process, from participating in workshops to demonstrating how the project is an investment for future tourism opportunities. Each step of construction ensures a deeper connection to the land and the communities that live there.

Sailing along the rain-swollen river by cayuco – Courtesy of Jennifer Malloy

The Naso Trail Takes Shape

One part of the project currently underway is the restoration of a 9-mile (15-km) ancestral trail on Naso tribal lands. Currently referred to as the Naso Trail, it will eventually connect six communities along the river and land, allowing travelers to visit on foot and by boat. By linking these communities, Benedetti also hopes to strengthen personal connections between villages as well.

“Each town has its own little separate circuit, so [the trail building] is a catalyst for [the Naso] to work together,” he says. “They are so used to doing their own thing; it consolidates the idea that they must work together.”

It’s the Naso Trail that I’ve come to discover as I step out of the cayuco at the Bonyic boat launch. Looking up at the looming ridge rising above the river, it’s hard to believe that a trail exists amidst the dense foliage and that it is an easy 2.5-mile (4-km) hike to the first community that the trail will connect. Also not immediately obvious is a petroglyph of a crescent moon, where part of the ridge has crumbled away. The Naso call this ridgeline “El Filo Media Luna,” which translates to Crescent Moon Ridge and is a potential name for the future Naso Trail.

“We want to help each community to develop their own identity and experiences,” says Benedetti. He recommends staying at least one night in a community for deeper immersion.

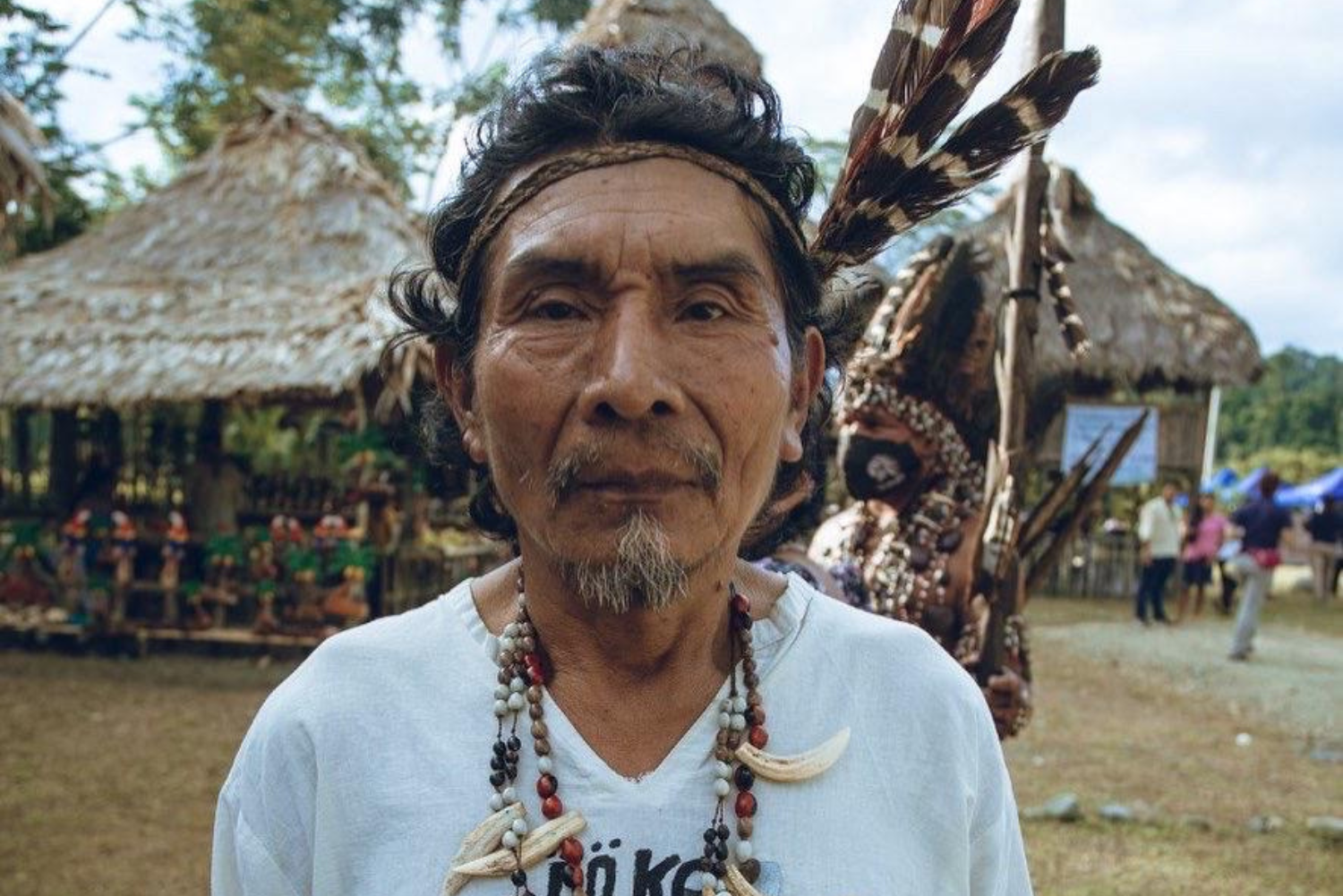

A Naso man in traditional headress. Courtesy of Jennier Malloy.

A Shaman Shares a Prayer

One night, my group is invited to join local men around the fire. We follow the scent of burning wood to a ramshackle collection of thatched buildings where festivals are typically celebrated. Bright flames reach into the night sky, and we settle around the smoldering heat of the fire to listen to local legends told by the village Shaman.

Adorned in a feathered headdress, he tells us of the healing properties of the wood of the Palo Santo tree, which he then dips in caraña hedionda (stinky resin) from the wood and burns before inviting us to a room above the bonfire to participate in a blessing. The unfamiliar words that he chants in the Naso language swirl around my head like the smoke he uses to bless me. I close my eyes and face my palms outward, breathing in, breathing out. I inhale the thick, acrid fumes and exhale anxiety, fear, and doubt.

We end with a prayer, which again I cannot understand, but can feel the immense beauty and gravity of. We embrace each other in a circle, feeling renewed, feeling reborn. I sleep untroubled that evening, despite having discovered a beetle the size of my hand next to my bed, an unexpected roommate.

In Bonyic, we stay at the Pousada Media Luna, which was built by and run by a collective of Naso women. It’s more than just a place to stay; however, it’s also an opportunity to fully experience the culture through traditional dancing, cacao-making workshops, visits to other communities (with the opportunity to meet the king of the Naso), carving demonstrations, and home-cooked cuisine sourced from local ingredients.

The Pousada not only provides financial independence to the women who run it, but staying here also supports the community as a whole.

Visiting communities on the Naso Trail. Courtesy of Jennifer Malloy.

Hope for the Future

According to Rosibel Quintero, the co-founder and current president, more visitors means more resources and a higher standard of living for everyone in the village. With the imminent construction of a university in the community of Seiyic, located 9-miles (15 km) upstream and an eventual stop on the Naso Trail, the hope is that every child will have the opportunity to pursue higher education.

Carlos Jimenez, the grandson of Isabel Sánchez (co-founder of the Pousada) and creator of Visit the Naso Territory, tells me that more tourism here will also help to economically develop the Naso communities. It will help create employment opportunities, promote local businesses, and strengthen cultural identity. However, he also stresses that the trail’s rehabilitation will ensure its conservation and the restoration process will not compromise the environment or traditions of the communities.

Eschewing Beaches for Cultural Immersion

With most tourists attracted to Panama’s islands while ignoring the mainland, Benedetti hopes the project will lure those looking for active experiences combined with Indigenous culture and traditions.

“It’s a beginning,” he says. “The start of something new.”

When I close my eyes, I transport myself to the village. To the swish of skirts and thump of feet during a traditional dance, to the scent of wood chips mingling with bubbling chocolate, and to the soothing patter of rain on the roof of the pousada.

In the era of overtourism, it’s the start of something new for visitors, too. Those eager to experience a seldom seen slice of Panama.

If You Go

Panamanian company Eco Circuitos organized all aspects of this journey, including the hiring of local guides and transportation options.

Bocos del Toro can be reached via a domestic flight from Panama City or by public bus.

Pousada Media Luna can accommodate up to 20 people and can be booked by contacting Rosibel Quintero (+507-6774-4631 or rosibelquintero48@gmail.com).

Jennifer Malloy is a Calgary, Alberta-based writer with a love for travel and outdoor adventure. She’s traveled around the world, but never tires of exploring her own backyard and can usually be found gallivanting in the mountains with her young son. Passionate about representing solo female and community-based adventure travel in her writing, she also hopes to encourage families to explore the world (preferably by foot) in a sustainable way. Follow Jennifer on IG @jenny__malloy.